ALT

ALT

30.04.25

What insights can be gained from learning space innovations in other countries for the situation in Germany? In this blog post, Prof. Dr. Katja Ninnemann shares experiences and insights from her research stays in Sweden, Singapore and Australia, summarizing them into concise hypotheses based on the constructive alignment model. It becomes clear that major changes require appropriate policy frameworks as a base and then often start with small initiatives. Thus, instead of waiting for perfect new buildings, new policy approaches as well as simple and local measures could provide the impetus for the next big learning space innovation Made in Germany.

At the conference dinner “Future Campus” in the cold and wet fall in Berlin, Oliver Janoschka and I agreed that I could write an article for the HFD Community about my research stays in Sweden, Singapore and Australia. I was certain that this would be an exciting overview of good practices in international learning space design.

However, during and in the follow-up to my learning (space) journeys, I realized that more photo series of innovative learning environments (alone) are no longer helpful in the context of German universities. Numerous national initiatives, projects and publications already provide a wide range of experiences in the development of model learning space concepts (see Prill, 2019, 2024). In this context, my research interest shifted more and more to the central question: What measures lead to the university-wide and cross-university scaling of learning space innovations as seen in Scandinavia, Australia and Asia, as well as in the USA and the UK? Building on the constructive alignment model, in this article I present my position on relevant frameworks based on three hypotheses.

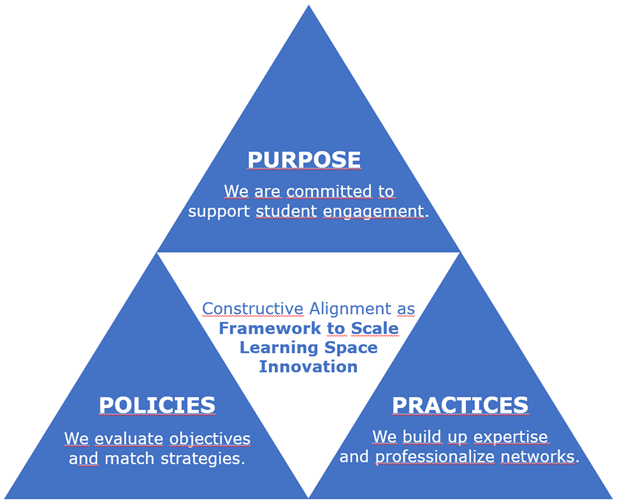

In the process of designing, planning and (re)constructing educational architecture as well as in the conception, development and implementation of courses, divers interests, attitudes and expectations of relevant actors and stakeholders can be identified, which are often not compatible with each other. Against this background, the constructive alignment model is used in pedagogical contexts to 1) make key learning outcomes transparent and 2) align assessment methods with 3) teaching and learning activities, thus harmonizing different perspectives and activities (cf. Biggs & Tang, 2011). For effective interventions to scale up learning space innovations in higher education institutions, the following three key aspects need to be considered: 1) purpose of an overarching objective, which needs to be aligned with 2) policies to categorize and evaluate strategies, as well as 3) practices to strengthen evidence-based and effective measures (see Fig. 1).

1) PURPOSE. We are committed to support student engagement.

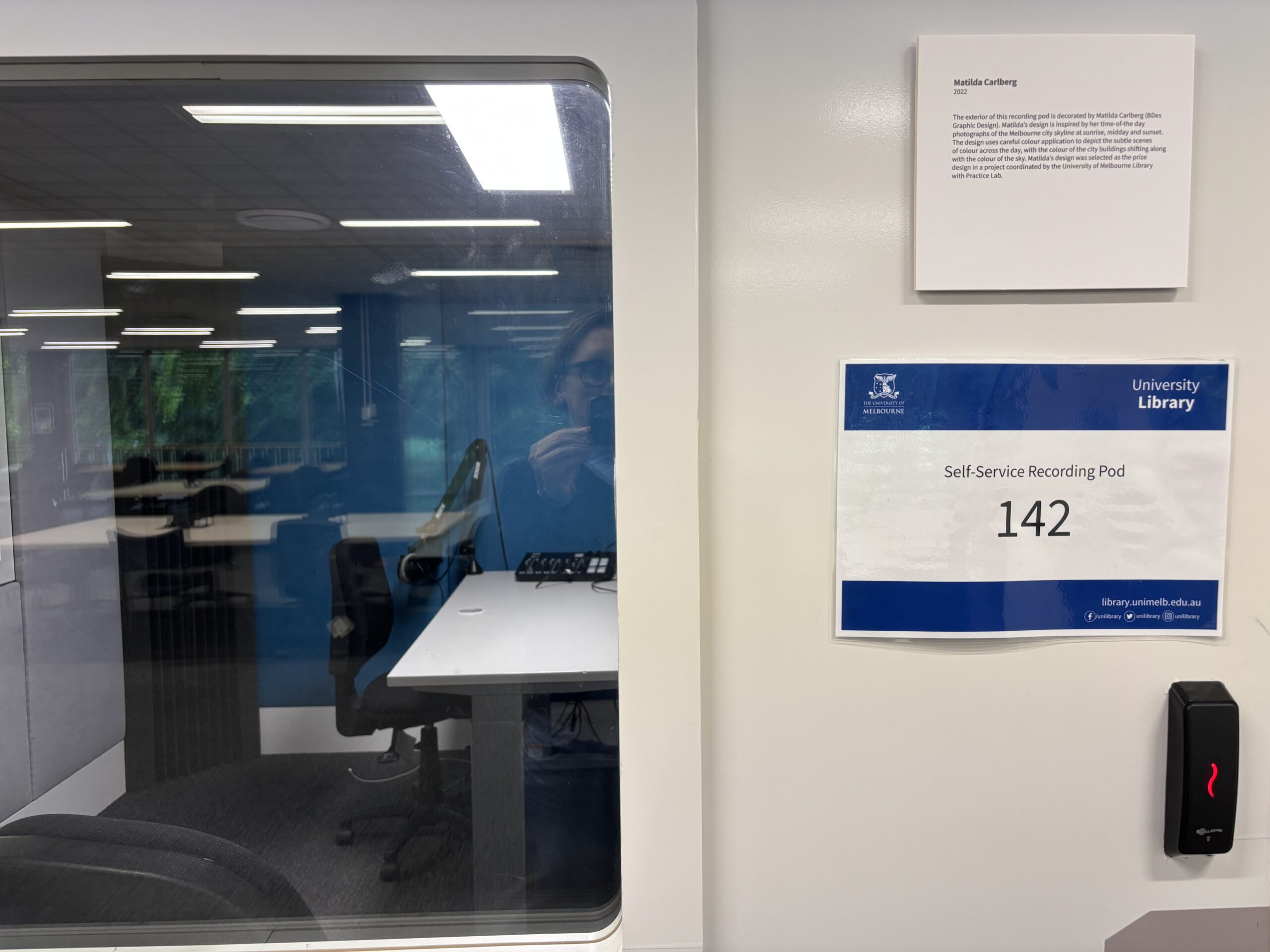

During my campus visits in situ as well as in workshops and discussions with interdisciplinary experts, it became clear that even in a supposed El Dorado for learning space innovations, financial constraints and administrative challenges persist when it comes to infrastructure projects. Searching for a common denominator for the “diffusion of innovation” (Rogers, 2003), a comment made at Melbourne University about the importance of student-centered approaches “to engage students with interactive learning activities” has stuck with me and led me to new findings.

Since the 1970s, various models and concepts, such as student engagement, student involvement, student experience, student participation and student partnership, have been discussed with growing interest in the literature and examined at the level of teaching and learning activities as well as in the context of community building and governance (cf. Holen et al., 2021; Bovill & Woolmer, 2020). Research findings show positive effects on well-being, satisfaction and student success as well as lifelong learning skills when students are engaged (cf. Bowden et al., 2021; Kahu, 2013). This means that students take responsibility for learning processes, are challenged through interaction with peers and teachers and are involved in extracurricular or institutional university activities (cf. Wenger et al., 2024).

Findings in this context have led to institutional reform initiatives in the USA, Canada, Great Britain, Australia and Scandinavia, among others (cf. Holen et al., 2021), which are the key to emerge learning space innovations. Against this background, I draw up the following hypothesis: a) The commitment to activate, integrate and participate students on academic, social and institutional level influences the degree of learning space innovations at universities.

It is therefore not surprising that student-centered learning space concepts have been developed and researched in precisely these countries and regions, which has led to innovations in the last 20 years such as Active Learning Environments and Flexible Learning Environments, the concept of libraries as learning centers and a holistic understanding of the university campus as a learning space (cf. Ninnemann, 2018, pp. 32-40).

2) POLICIES. We evaluate objectives and match strategies.

Studies on student-centered learning environments show that investments are worthwhile, as they increase student satisfaction and well-being, lead to an improvement in learning comprehension and learning outcomes and promote social integration and a sense of belonging among students (see de Borba et al., 2020; Ninnemann, 2018; Matthews et al., 2011; Ninnemann, in press); this is also impressively demonstrated by the experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic when the university campus was not available as a place for encounter. Despite these findings, already established and evidence-based learning space concepts have not yet been significantly disseminated in the German higher education landscape in contrast to the international context.

This suggests that universities should be encouraged and challenged to establish effective strategies in order to support student engagement by means of long-term and sustainable processes and structures – which also includes the (further) development of learning environments. In this context, I draw up a further hypothesis: b) The evaluation of measures to activate, integrate and involve students at academic, social and institutional level influences the scaling of learning space innovations at universities.

When researching how student engagement is evaluated in the international context, you cannot ignore the National Survey of Student Engagement (cf. Pike, 2013). NSSE has been used in the USA since 2000 and in Canada since 2004 and has served as a base for the development of evaluation tools in Australia, the UK, Ireland, South Korea, Chile, South Africa and China, among others (cf. Fhlannchadha, 2022). Ten engagement indicators in four categories and six high-impact practices support the evidence-based development and comparability of higher education institutions.

In Scandinavia, the conditions that promote learning spaces are different; student engagement is deeply embedded in academic culture (cf. Holen et al., 2021; Alaniska et al., 2006). In Sweden, for example, it is legally required that students participate in decision-making at all levels of higher education institutions (cf. Barrineau et al., 2019; Kettis, 2019). Similarly, students in Finland and Norway also have a strong voice in decision-making bodies and in the strategy development of higher education institutions as an expression of democratic values and practices (cf. Petronienė et al., 2024; Ursin, 2019; Alaniska et al., 2006). In Norway, for example, student involvement and student partnership are a key criteria for participating in the prestigious Centres for Excellence in Education Initiative (cf. Ski-Berg & Stabell, 2024; Holen et al., 2021).

3) PRACTICE. We build up expertise and professionalize networks.

The developments and interrelations outlined so far demonstrate that learning space innovations are deeply embedded in the DNA of universities, but also affect overarching (educational) policy decisions and social attitudes. Due to this complexity, the development and expansion of expertise for evidence-based decisions and measures, as well as the professionalization of networks, are necessary. In this context, I draw up a final hypothesis: c) The continuity of knowledge development and knowledge transfer beyond temporary project statuses influences the effectiveness and sustainability of learning space design measures at universities.

At Melbourne University, for example, two professorships for Learning Environments have been established, which are anchored in the Faculty of Architecture, Building & Planning and the Faculty of Education. With the associated members of the Learning Environments Applied Research Network (LEaRN), an interdisciplinary team ensures excellent research and teaching as well as the transfer of research findings to industry and politics. Subsequently not only the qualitative and quantitative research output and the promotion of young scientists is impressive, but also the successful function as consultants in numerous award-winning projects of educational architecture. Thus, from my own experience, it is incomprehensible that there are chairs and professorships for healthcare architecture at German universities, but not for educational architecture. I personally still benefit greatly from the networking and research activities during my guest professorship Corporate Learning Architecture at the Technical University of Berlin in 2019/2020.

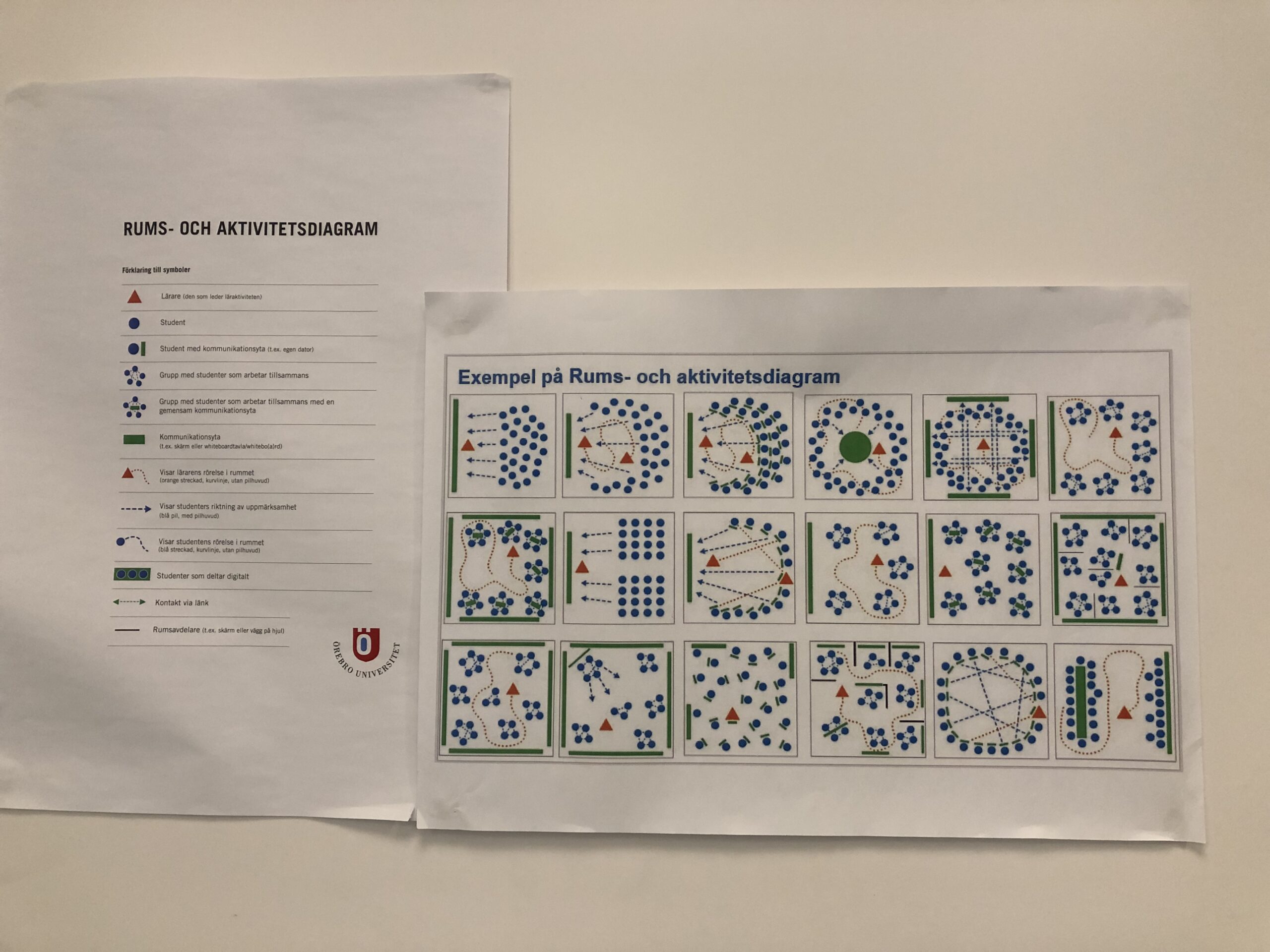

In Sweden, Akademiska Hus serves as professional coordinator of a network for research and practice in order to orchestrate the interdisciplinary and cross-university exchange. As a state-owned company that owns, manages and develops real estate at several universities, it also manages and finances, among other things, the national community “Rum för Lärande”. More than 500 members are connected by seminars, workshops and lectures, promoting research activities as well as analyzing and processing good practices. Linking pedagogy, space and technology, ideas and findings can be integrated directly into project practice, leading to compelling examples of innovative university buildings. In my opinion, it is also possible to establish and consolidate a comprehensive network through institutionally anchored curation in Germany. The establishment of the Communities of Practice for future-oriented learning spaces, funded by Stifterverband and Dieter Schwarz Foundation (2023-2024), has already provided a good starting point, but needs an acting host.

(OUT)LOOK

Considering the three hypotheses for measures to scale learning space innovations at universities, there is a lot to do to establish and expand student-centered processes and structures. However, but even in the early days of internationally widespread learning space innovations, the changes started small and were based on individual ideas and/or initiatives to promote student engagement. In 2001, for example, a small Learning Café at Glasgow Caledonian University was the starting point for Les Watson to conceptualize the library not as an information center but as a learning center to offer students a wide variety of places for different learning activities (see Ninnemann, 2018, pp. 27, 159). And the idea of SCALE-UP classrooms originated in 1997 in Robert Beichner’s physics lectures at North Carolina State University to enable student-centered activities in teaching and learning settings (cf. Foote et al., 2014).

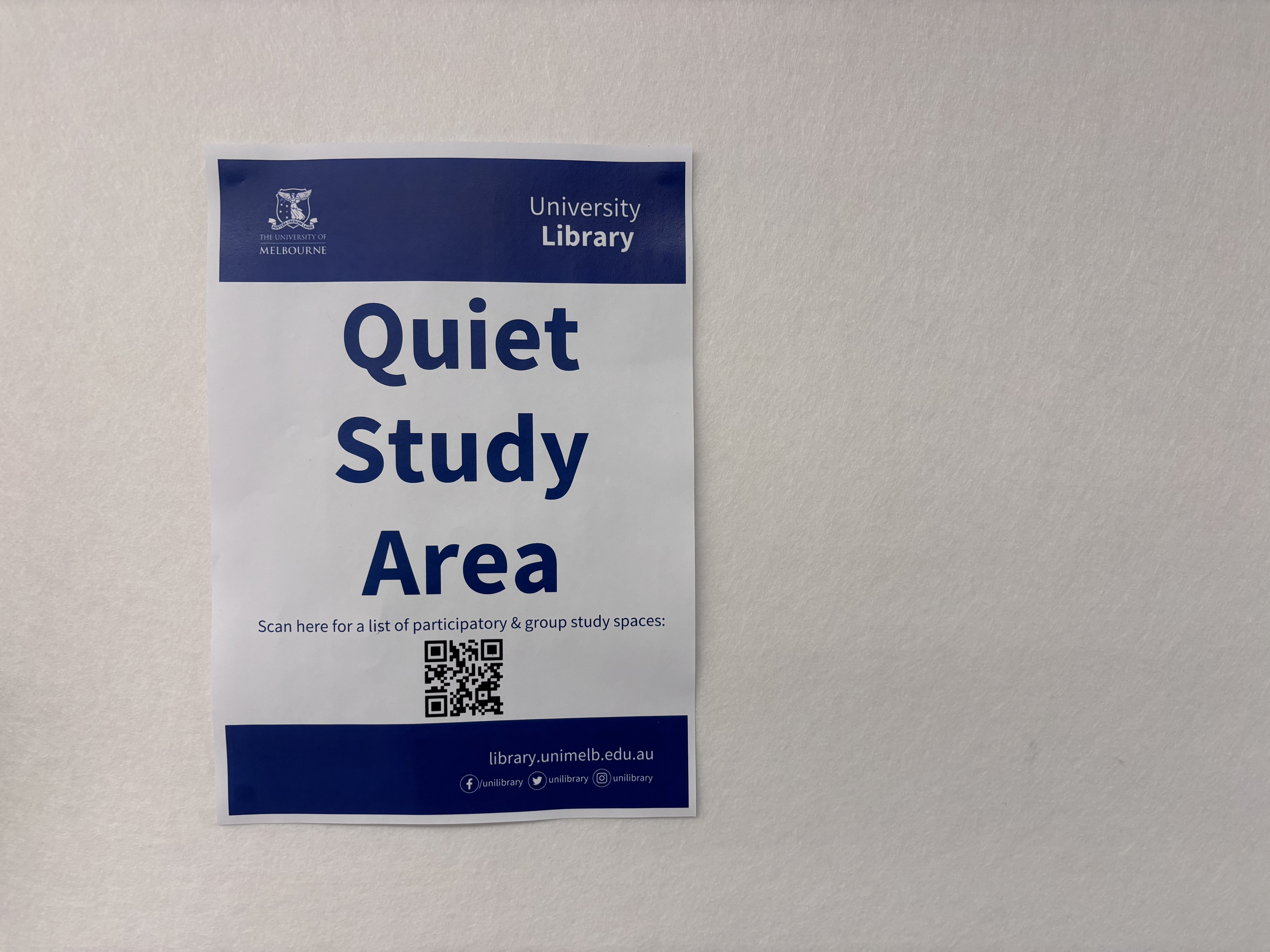

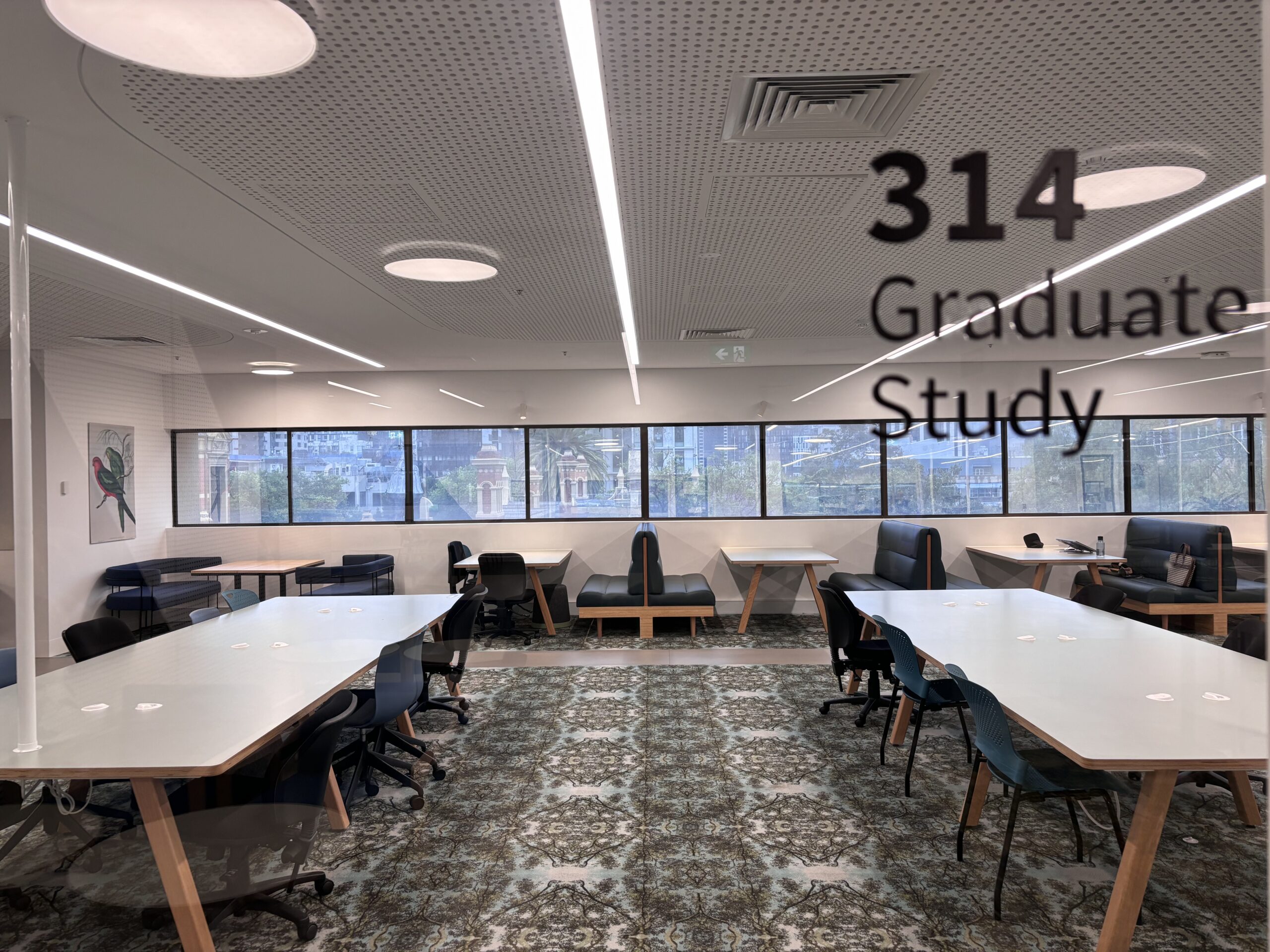

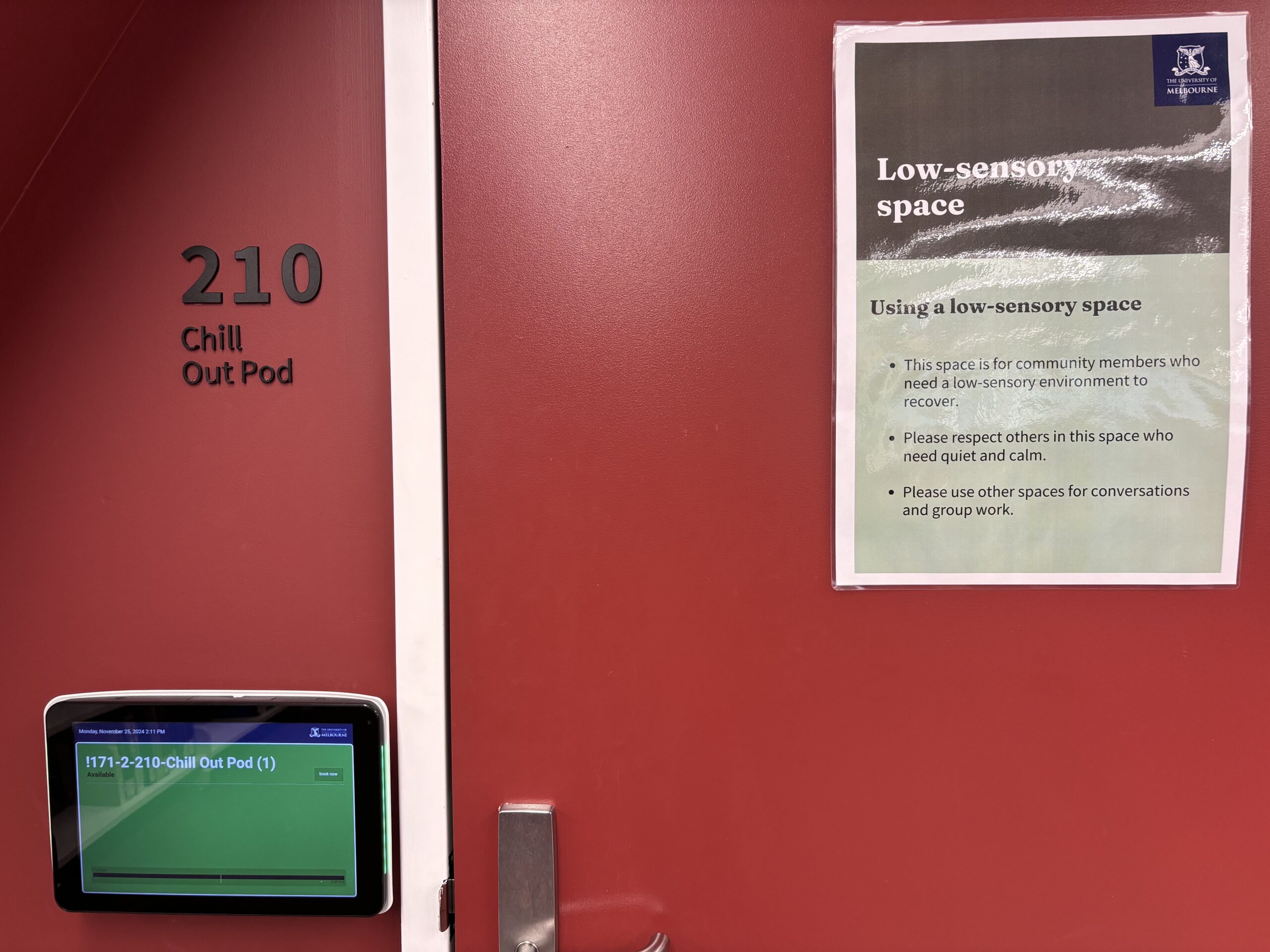

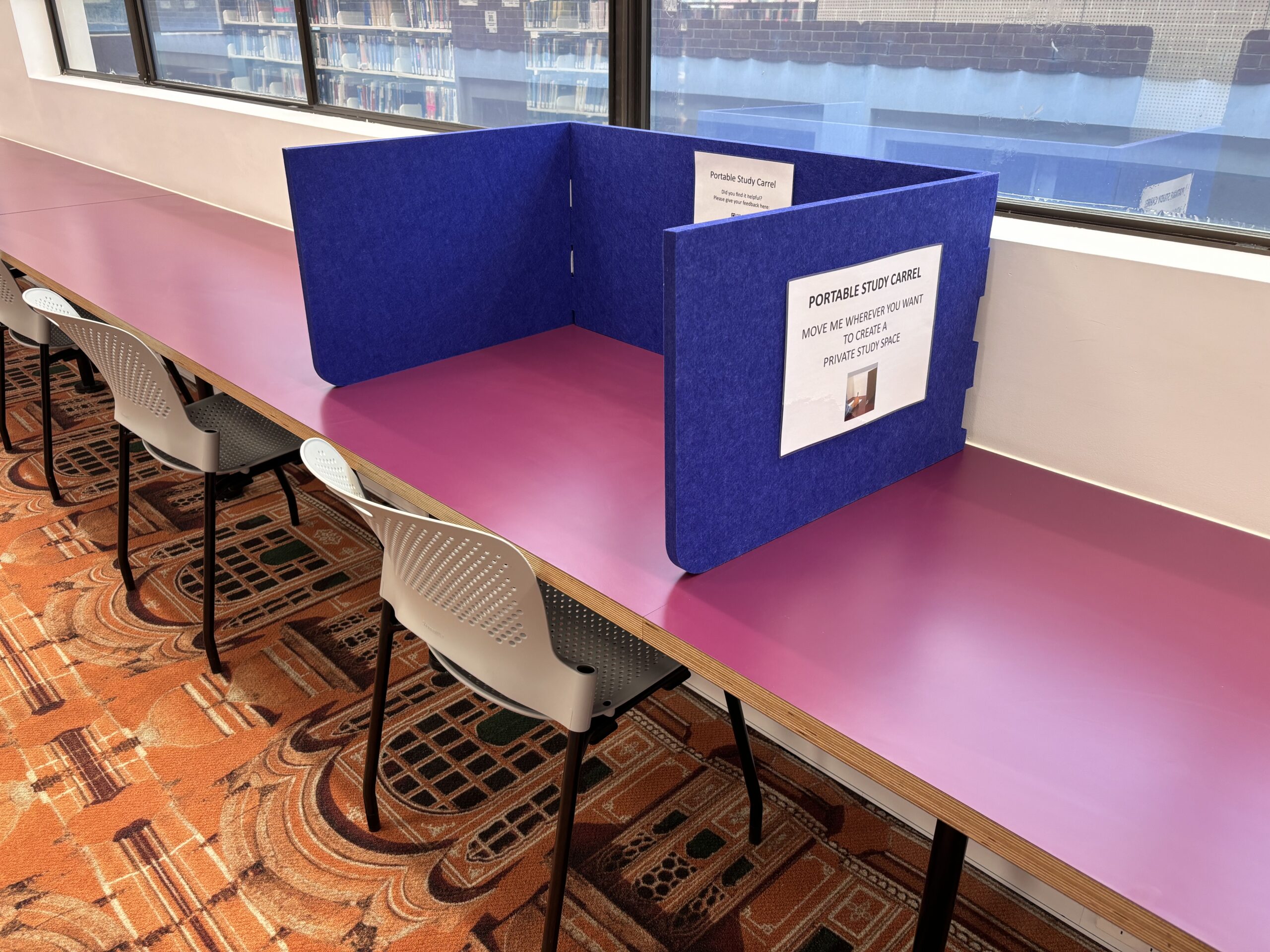

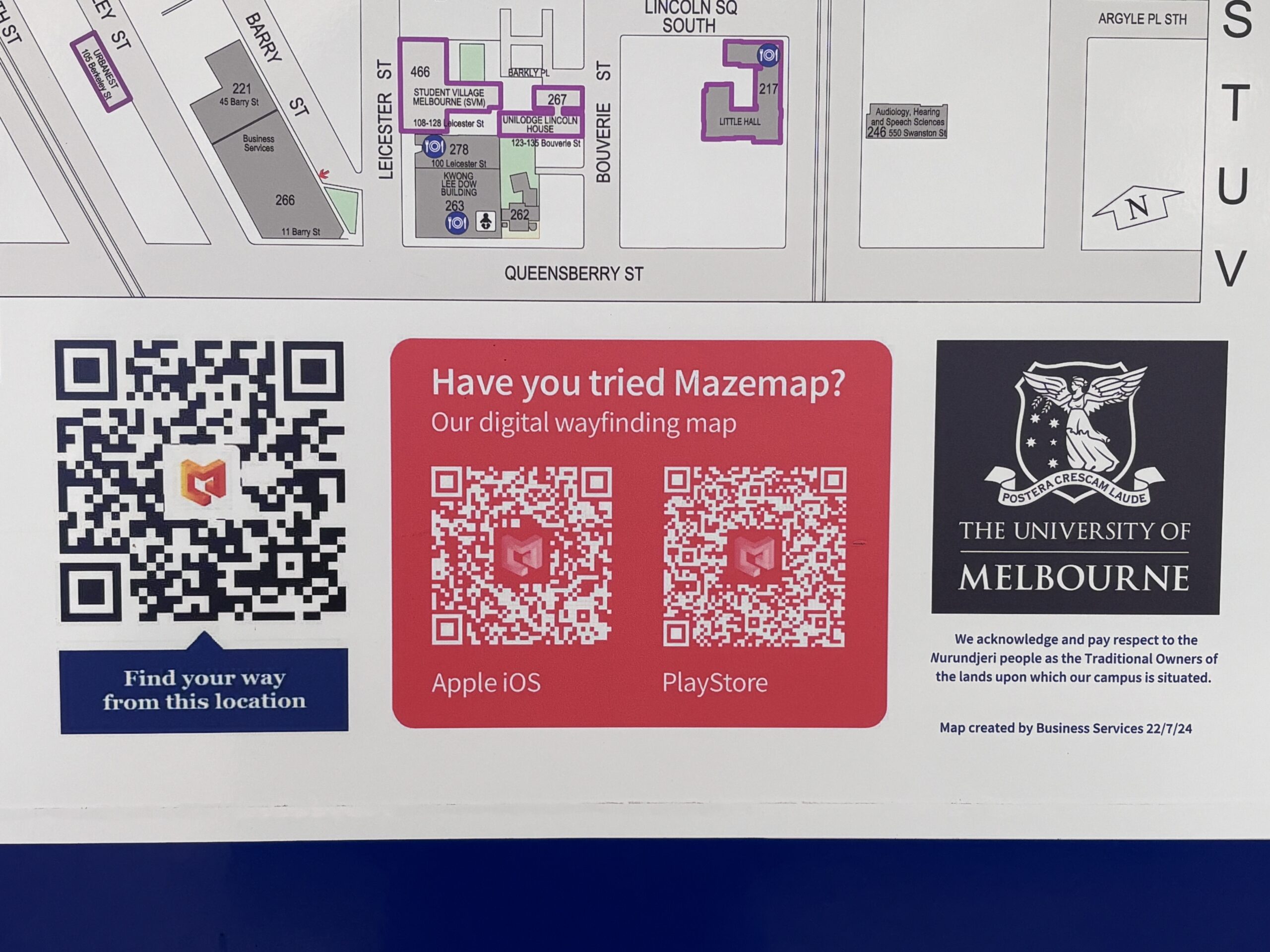

Thus, if you walk around the university campus with an open mind, you will find many opportunities to support student engagement. And it can be quite helpful if there is no new building available or even on the horizon. For example, colleagues at Melbourne School of Design miss their old building, as there was more freedom to experiment, try things out, and even fail than in the new (award-winning) Glyn Davis Building. With this in mind, instead of a photo collection with showcases, I have put together photographic insights with simple ideas and measures. True to the motto ‘better done than perfect’, it’s worth just getting started. And perhaps one idea will become the next big thing Made in Germany.

Photos Focus on student engagement : Small measure, big impact

Literature

Alaniska, H., Arboix Codina, E., Bohrer, J., Dearlove, R., Eriksson, S., Helle, E., & Wiberg, L. K. (2006). Student involvement in the processes of quality assurance agencies (Workshop reports No. 4; S. 1–48). European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education. https://www.enqa.eu/wp-content/uploads/Student-involvement.pdf

Barrineau, S., Engström, A., & Schnaas, U. (2019). An Active Student Participation Companion. Uppsala University.

Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning at University: What the Student Does (4. Aufl.). Open University Press.

Bovill, C., & Woolmer, C. (2020). Student engagement in evaluation. Expanding perspectives and ownership. In T. Lowe & Y. E. Hakim (Hrsg.), A Handbook for Student Engagement in Higher Education: Theory into Practice. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429023033

Bowden, J. L.-H., Tickle, L., & Naumann, K. (2021). The four pillars of tertiary student engagement and success: A holistic measurement approach. Studies in Higher Education, 46(6), 1207–1224. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1672647

de Borba, G. S., Alves, I. M., & Campagnolo, P. D. B. (2020). How Learning Spaces Can Collaborate with Student Engagement and Enhance Student-Faculty Interaction in Higher Education. Innovative Higher Education, 45(1), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-019-09483-9

Fhlannchadha, S. N. (2022). The Results of the StudentSurvey.ie. Trends Over Time Research, 2016-2021. All Ireland Journal of Higher Education, 14(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.62707/aishej.v14i1.677

Foote, K. T., Neumeyer, X., Henderson, C., Dancy, M. H., & Beichner, R. J. (2014). Diffusion of research-based instructional strategies: The case of SCALE-UP. International Journal of STEM Education, 1(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-014-0010-8

Holen, R., Ashwin, P., Maassen, P., & Stensaker, B. (2021). Student partnership: Exploring the dynamics in and between different conceptualizations. Studies in Higher Education, 46(12), 2726–2737. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1770717

Kahu, E. R. (2013). Framing student engagement in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 38(5), 758–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.598505

Kettis, Å. (2019). Students as partners in Swedish higher education: A driver for quality. In Student Engagement and Quality Assurance in Higher Education. Routledge.

Matthews, K. E., Andrews, V., & Adams, P. (2011). Social learning spaces and student engagement. Higher Education Research & Development, 30(2), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2010.512629

Ninnemann, K. (2018). Innovationsprozesse und Potentiale der Lernraumgestaltung an Hochschulen: Die Bedeutung des dritten Pädagogen bei der räumlichen Umsetzung des „Shift from Teaching to Learning“. Waxmann.

Ninnemann, K. (2025). Erweiterung von (Handlungs-)Räumen der Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung über die Perspektive eines relationales Raumverständnisses. Journal für LehrerInnenbildung, 25(1). 18-29

Petronienė, S., Juzelėnienė, S., Tautkevičienė, G., Eyjólfsdóttir, E. B., Stebbins, R. W., & Dovidonytė, R. (2024). Promoting student engagement: Insights from Iceland, Lithuania, and Norway. Frontiers in Education, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1430247

Pike, G. R. (2013). NSSE Benchmarks and Institutional Outcomes: A Note on the Importance of Considering the Intended Uses of a Measure in Validity Studies. Research in Higher Education, 54(2), 149–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-012-9279-y

Prill, A. (2019). Lernräume der Zukunft: Vier Praxisbeispiele zu Lernraumgestaltung im digitalen Wandel (Arbeitspapier No. 45). Hochschulforum Digitalisierung. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3484654

Prill, A. (2024). Zukunftsorientierte Lernraumentwicklung. Handlungsempfehlungen für die Begleitung partizipativer Prozesse in der Konzeptionsphase (Arbeitspapier No. 80). Hochschulforum Digitalisierung. https://hochschulforumdigitalisierung.de/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/HFD_AP_80_Zukunftsorientierte_Lernraumentwicklung_digital.pdf

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of Innovations (5. Aufl.). Free Press.

Ski-Berg, V., & Stabell, E. M. (2024). Enabling and exploiting student expertise: The case of a Norwegian centre for excellence in education. Studies in Higher Education, 0(0), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2024.2352607

Ursin, J. (2019). Student engagement in Finnish higher education: Conflicting realities? In Student Engagement and Quality Assurance in Higher Education. Routledge.

Wenger, K., Russel, A., & Kienzie, J. (2024). A Friendly Guide to Student Engagement. National Survey For Student Engagement.

Author:

Prof. Dr. Katja Ninnemann studied architecture and urban planning and completed her doctorate on innovation processes in context of learning space developments at universities. After her guest professorship Corporate Learning Architecture at TU Berlin, she was appointed as Professor of Digitalization and Workspace Management at HTW Berlin University of Applied Sciences. As an expert on spatial design practices and innovation processes, she is currently researching on organizational processes and structures in Higher Education to establish evidence-based hybrid learning and working environments.

Nina Horstmann

Nina Horstmann

Theresa Sommer

Theresa Sommer